Where Are We At With Nuclear Fusion?

Nuclear fusion is the holy grail of power production. It is what powers the Sun and all the stars we see in the night sky.

For the past 80 years, scientists have been saying it's been only 30 years away from being perfected. Except now, with the massive projected electricity demands of AI and the scaling back of fossil fuel use, it could be close to reality.

Our guest is Dr Warren McKenzie, Managing Director of HB11, a small Australian company looking to power the world into the future.

The artistic re-use of what's left of the 500 megajoule Canberra Homopolar Generator. It was developed during 1951-1964 at the Australian National University, under the direction of Sir Mark Oliphant. The CMG was dismantled in 1985. Image: Peter Ellis.

The British team of the Manhattan Project that developed nuclear weapons, led by Sir Mark Oliphant (second from front left).

Image:GetArchive

The target core of the National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, California, USA

David (00:10)

How great is fusion?

(Background jazz fusion muzak playing)

Okay, not that sort of fusion, nor the kind that creates hot dog sushi or taco lollipops. Hello, and welcome to Where Are We At With? I'm David Curnow.

The global electricity demands are growing exponentially, whether it's air conditioning in developing countries or places affected by climate change, or the big mover in power use, data centres. Every time you pull out your smartphone to check the weather or ask AI to generate an image of, say, hot dog sushi or taco lollipops, a data centre somewhere is using huge amounts of energy. The International Energy Agency says data centre power use alone will triple in the next 10 years. How to provide that power in a way that doesn't burn polluting fossil fuels or use rare earth minerals locked away by China? How about by harnessing what's thought to be the greatest clean and abundant source of energy available, nuclear fusion, capable of releasing more power than its nuclear neighbour, fission, but without those pesky little side effects like meltdowns and radiation that lasts for millennia. The global race is on to perfect fusion and Australia has its own entrant. HB11 is a private company with the modest ambitions of changing the world as we know it, using a special technology.

I spoke to HB11's Managing Director and co-founder Dr Warren McKenzie to find out where are we at with nuclear fusion.

David (01:56)

Dr Warren Mackenzie, thanks very much for joining me today.

Warren (01:58)

G'day David, thanks for having me.

David (02:00)

We'll get on in a moment to what your company is doing, what your background is, and I guess what the rest of the world is doing when it comes to where are we at with nuclear fusion. The first question has to be the simplest, and I use that term advisedly. What is nuclear fusion?

Warren (02:13)

So nuclear fusion is joining atoms together, which is in contrast to fission, which is splitting atoms up. In both cases, they produce energy and in about the same energy density. So they both allow a very, very small amount of fuel to produce a lot of energy, which is why we're really interested in both fission and fusions as two forms of nuclear energy.

David (02:37)

Okay, when do we first know about fusion? When do we first think that this is an option?

Warren (02:42)

Fusion was discovered, I don't quote me here, but around about the 30s by Rutherford and also an Australian, Mark Oliphant. Or at least that were the first observations of this effect, which produced quite a lot of energy in a very small reaction.

And since then, it's been engineered into a lot of different things as methods for making radioisotopes, things that we don't necessarily want in peaceful times, as well as now the big opportunity, which is essentially clean energy.

David (03:17)

Absolutely, and it is such an important thing. Very quickly, I do want to talk about just the differences in process here, because in my limited understanding, very limited, I see that lighter atoms are preferred or likely to be better for fusion and heavier for fission. Do we know why that is?

Warren (03:26)

Yeah, atoms are made from protons and neutrons with electrons orbiting around the side. Now those are bonded together with a nuclear force. So that nuclear force, is much lower for much, much lighter atoms and a little bit lower for much more heavy atoms, so uranium and things that you would use for fusion, fission sorry. So the heavy atoms are relatively easy to split and therefore eject energy. And similarly for fusion, if we are looking to join those atoms together, that process requires much, less energy for the lightest of elements right down the other end. So if you open a nuclear textbook, that would talk about the nuclear binding energy. And you can see that the things in about the middle of the periodic table, you know, have high binding energy. So they're not particularly useful for practical nuclear applications, but the light ones are useful for fusion because they're the easiest to join. And the heavier ones are useful for fission because they're easy to split because of that nuclear energy.

David (04:28)

Okay. It's like a lot of things. Sometimes it's easier to break things than to put them back together.

Warren (04:33)

That's very true.

David (04:34)

As somebody who is not a Nobel Prize winning physicist, do different elements contain different amounts of that nuclear binding in terms of the potential energy?

Warren (04:42)

Absolutely. So the energy that's produced through splitting or binding atoms absolutely is different. Quite often they are like chemical processes. are a multi-step process before they actually eject energy. And I guess in the case of hydrogen-boron fusion, you take a hydrogen, which is a proton, add it to a boron, it turns into a carbon and then decomposes into three helium. So it's a few step process and each one of those releases a little bit of energy.

David (05:08)

I followed you that far, we'll find out what's more in a moment. Alan Kohler from the ABC wrote an opinion piece for Aunty in 2025, and he said he was speaking to superannuation investment funds who were investing heavily, and they were describing it as the biggest potential change in the world's energy mix we've seen in a lifetime. How much money around the world do we think is being invested in nuclear fusion at the moment?

Warren (05:11)

In total, in the Western world, it's around about 15 billion US dollars. It's about three billion dollars per year going into fusion programs, but it's about to ramp up a lot. Really, really a lot. And that's coming from governments who have been long planning milestone based public-private partnership programs, which is a long way of saying, weighing in heavily to win the race for the future fusion industry. The reason it's so important for these guys is that most governments know that energy and quality of life are essentially correlated exceptionally well. Whoever has the most energy is gonna lead the highest quality of life because energy itself runs the economy. And that's absolutely more true now than any time in the past, because we need new energy sources because we're trying to wrap down fossil fuels. And everyone's seeing the emergence of AI and data centres, which are very, very energy hungry. So if we want to own our own knowledge, thinking, and data communications, we need a lot of energy for that.

David (06:30)

And so how big a deal then is being able to come up with a source of energy which is both extremely efficient in what it produces and also, I suppose, likely to contaminate as fossil fuels or even fission reactors when things go wrong.

Warren (06:43)

Well, it's not an easy task. If it was easy, someone would have done it by now, right? It's very scientific. I guess in contrast to the people developing fission, that's a relatively straightforward process where once you can make the material, it just produces energy on its own. Fusion is a lot different in that you need to put a lot of energy into a very, very structured target to be able to actually ignite a fusion burn and actually get that energy out. So fusion is much more scientifically and engineering more complicated, but in the same sentence, I'll say that it's far safer, cleaner, and the fuels are far, far more abundant than what we use for fission. And the by products that are produced don't have 100,000 year half lives which represent the waste problems.

David (07:27)

You mentioned the fact that it's mechanically, scientifically harder. And as we know, the process of fusion was observed at least or postulated a long time ago, but we got to fission pretty quickly from that point. We still haven't quite, and we'll talk about some of the efforts soon, but quite got to fusion. What's changed though to make all of this effort ramp up to say, look, we actually think we can do this?

Warren (07:49)

We've actually got scientific results showing that it works. It's showing that it can be worked in a, a controlled way. There are uncontrolled ways that, you know, we may not want to talk about on your podcast that absolutely work.

David (08:01)

Yes, uncontrolled fusion is what you get in thermonuclear weapons, hydrogen bombs, like the biggest bomb ever detonated on earth, Soviet's Tsar Bomba in 1961.

Warren (08:13)

But for controlled fusion that we will need for energy, the first demonstrations of that have been achieved just back in late 2022. And that has given the whole industry and the world a big motivational kick to try and make fusion work because it's the only energy source that has the scale of fossil fuels.

David (08:32)

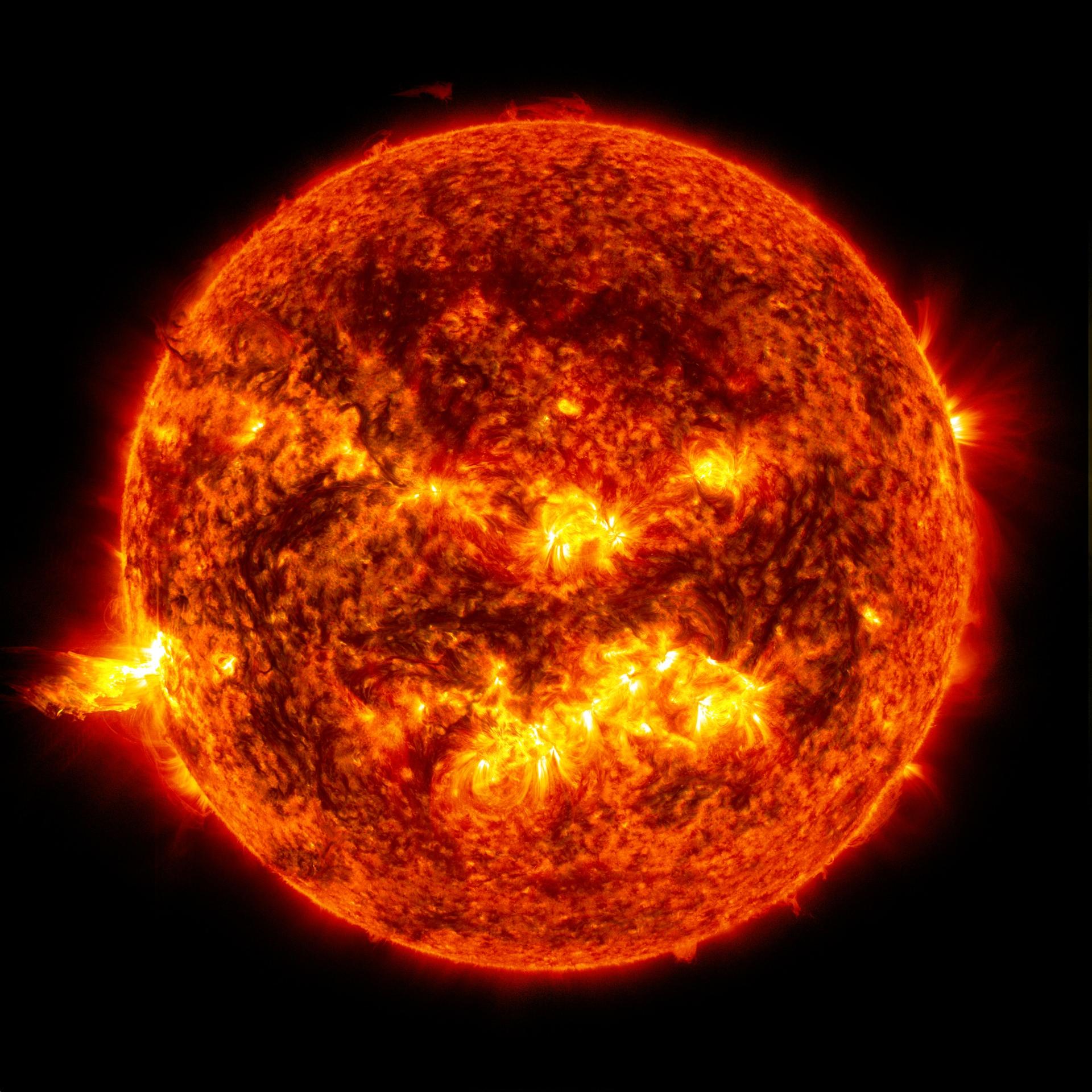

And let's take that a little bit of a step back because talking about fusion, we know it works in part because we see it every day. How does it work for the stars, like our star, the sun?

Warren (08:43)

Well, fusion, the fusion process itself needs a lot of temperature and a lot of pressure and also time. So here on earth, we need to make that pressure ourselves or we need that time that, you know, we produce that time ourselves and we can talk about the Lawson criteria. On a planet, you have gravity or a star, have a lot of gravity and that gravity produces a lot of pressure within the centre of that star, enough to produce fusion processes. And those fusion processes create a lot of energy and that energy keeps it hot, which produces more fusion reactions. And in the case of the sun, it's got so much energy that it provides all of the energy for life on earth that we see that gives us sunburn when we don't put our sunscreen on.

David (09:27)

But stars like the sun, they're also effectively using fuel.

Warren (09:31)

Yes, so the most abundant material in the universe is hydrogen. There are different isotopes of hydrogen and being the lightest elements, they're also the preferred fusion fuels. So I guess regular hydrogen is a proton, heavy hydrogen, is called deuterium, also has a neutron, and super heavy hydrogen, which is tritium is the, you know, the third natural, form of hydrogen, which is used for fusion fuel. So the most common fusion fuel is heavy hydrogen bonded with super heavy hydrogen. So deuterium with tritium. And that I believe is the primary fusion reaction that powers the stars in the sun.

David (10:08)

And does any of the deuterium or tritium occur naturally on Earth?

Warren (10:13)

Deuterium absolutely occurs naturally at certain percentage of seawater, which is where most of the hydrogen is would be deuterium. Tritium is a little bit different because it decomposes. It's a little bit radioactive. It decomposes into alpha particles, but because it decomposes, it doesn't occur naturally on earth. So, you know, just like anything that's going to deteriorate, you literally don't find it naturally and you have to produce it. And there are various ways that we can do that.

David (10:42)

Okay, we might get into that later. We might not because it isn't necessarily relevant to the process you're using, although others are. We mentioned there The Lawson Criteria. Why is that important and what does it measure?

Warren (10:54)

Okay, so The Lawson Criteria talks about the fusion or what we need to ignite a fusion reaction or to create fusion reactions as they occur. So they need temperature, temperature, time and pressure. So if we have very high pressure, we might need less temperature or can manage with less time, we have very high temperatures, we can probably get away with low densities in a long time. And that's the case with magnetic fusion. For laser fusion or inertial confinement fusion, you have very, very high densities. So therefore the fusion reactions take place in a very short amount of time, but also with a… also can reach very, very high temperatures in a short amount of time that the burn takes place. So temperature, pressure, time, if we can get the product of those to a certain level, we can ignite fusion. And most of the fusion approaches that we see today are trying to optimize or different ways of achieving that criteria in a fuel.

David (11:49)

Okay, when we're talking temperature, I mentioned the sun, stars. My understanding, and again, limited knowledge here, is they're hot. How hot?

Warren (11:57)

They're very hot

David (11:58)

This is more than just your regular blowtorch, right?

Warren (12:01)

This is more than ever at regular blowtorch. So we're talking in the tens of millions of degrees, which I believe is what the sun is at, is burning out at least at the surface. For fusion, typically those temperatures would be in the tens of millions of degrees for deuterium tritium. For other fuels like hydrogen boron, they're well into the hundreds of millions of degrees. So reaching those temperatures to make fusion possible, fusion fuel be able to burn is a scientifically difficult challenge.

David (12:30)

Yet my oven doesn't have that setting on it. Are there materials on earth that can even withstand that sort of pressure?

Warren (12:32)

No, no. Well, no, absolutely not. All of this field, we call it plasma physics. And what we mean when we say plasma physics is, there are no materials, everything is a plasma. Plasma is essentially a gas particles that don't necessarily have the electrons and they automatically repel each other. So they're not solids or liquids once they're actually in a state where they can burn, they're simply too hot. And, you know,…

David (12:58)

So too hot to burn?

Warren (12:59)

Too hot to burn. And a plasma would, know, very similar to the fluorescent light bulb that I have above me. That's a gas, it's not a material, it's a gas that is fluorescing as a plasma. So these are not materials there in magnetic fusion, these are essentially suspended plasmas in inertial confinement fusion, they're very, very dense plasmas, but the reaction takes place in such a short amount of time, they're held together literally by their inertia. They're burnt before they even have the ability for their momentum to expand and release into the outside world. Short time. High pressure short time.

David (13:31)

Okay, so let's talk then about the initial method, some of the techniques that have been tried. talk about magnetic and creating these plasmas to get to certain temperatures. How do you get them there and what have been the techniques that have been tried by other research organizations?

Warren (13:47)

Yeah, so two basic genres of fusion are magnetic fusion or inertial confinement fusion, which is normally done with lasers. I call it laser fusion.

CLIP FROM AUSTIN POWERS: INTERNATIONAL MAN OF MYSTERY

“In essence, a sophisticated heat beam which we call a “laser”.

Warren

So magnetic fusion, I refer to it as a glorified fluorescent light bulb. So we're taking a low density plasma, a small amount of gas injected into a very large donut shaped or more complex shaped device that has very, very strong magnets. Now the reason we need those really strong magnets is that gas gets really, really hot, tends to maybe hundreds of, a hundred million degrees. And it needs that for that gas to turn into a fusion flame to produce energy. That gas is so hot, can't touch the walls. We need it suspended. If it touches the walls, bad things are gonna happen. And to have the magnets that we need that strong, need to be superconducting magnets. And anyone who knows about superconductors know that they cryogenically cooled. So if the magnets get too hot, then the magnets stop working, then you have a lot of problems with an entire system if there is a quenching of it. But essentially, the tokamak, there's also stellarators and a few other magnetic fusion devices, essentially are very, very large magnets that suspend a small amount of gas at quite high temperatures, not high pressures, but for a very long time. And those can burn for seconds to minutes. Now laser fusion or inertial confinement fusion is very, very different. So we would take a pellet, a very, very small pellet, maybe a millimetre in size. We would shoot lasers at it. Those lasers do a couple of different things. If you imagine, if you imagine my coffee cup here, this is the fuel, we shoot the laser from this side. The laser will explode, this is our fuel pellet. The laser explodes the site. Now some of that will explode outwards, but conservation of momentum, some of it's gonna explode inwards as well. So if we put lots and lots of magnets all around the side of that, some of those materials as we shoot the laser at them is gonna explode inwards and as that plasma explodes inwards, it reaches many, times the density of that material as it would be solid. Now, high density. When we've got those high densities, that means that we have a very, very short amount of time. Well, it means that the fusion reaction can take place in a very, short amount of time. That time is short enough for that burn to take place before these atoms that have been imploded actually have time to repel each other and actually go out. So we're talking literally in the tens of picoseconds, we would have a propagating burn through maybe a millimetre size target that might produce gigajoules of energy. Gigajoules, we're talking probably not the best analogy, but that would be a small truckload of coal in a one millimetre size pellet is released from that one fuel pellet implosion.

David (16:33)

And picoseconds, let's work out our timing here. How many, how small do we break the second here?

Warren (16:46)

All right, so nanosecond is a billionth, picosecond is a trillionth, so a few tens, 10 trillionths of a second. All of the processes over and done with.

David (16:55)

Wow. they say it's, you don't want to be done too quickly, but I suppose that's necessary, but it releases the energy all the same.

Warren (17:03)

It releases the energy in an instant and that has to be captured. Magnetic fusion versus inertial confinement fusion is very, very different. So magnetic fusion, you've got one flame that burns relatively slowly and has some time to collect the energy. Whereas inertial confinement fusion, you inject the pellet, you shoot lasers, you get some energy. Then you shoot the next pellet, you shoot the lasers and get next to it. So that energy is released also in a very, short amount of time. And there are engineering challenges of capturing that energy, which has a very, very high energy density as a function of time. It all comes out in a few tens of picoseconds.

David (17:36)

Okay, there's a couple of things there that we need to get to in a moment, but I do want to mention you talked about the fact that for magnetic confinement we are talking longer periods of time. That's why when we see the results of some of those who've been involved, China, some of the European advances with the work they're doing, they talk about measuring in minutes at times, 10 minutes in cases.

Warren (17:52)

Yeah, magnetic fusion has been the focus of fusion efforts around the world for much, longer than inertial confinement fusion. Despite the fact that magnetic fusion has not actually achieved a propagating burn, at least to reach net energy gain. Whereas inertial confinement fusion has, just…

David (18:15)

Drops mic.

Warren (18:17)

There's big programs, the most famous one is ITER which is based in Cadarache and France. an experiment that was designed in the 90s. It was originally established alongside the International Space Station, I believe, as a means of scientific collaborations in order to repair relations between the US and the Soviet Union and other parts of the world. Now the difference is International Space Station has been very successful. Itter is not finished yet. It's still got another, I'm not exactly sure how many years, but at least a decade before it's gonna be turned on. So it's a very, very complicated machine. There's a lot of engineering, a lot of understanding around these devices. One of the bigger problems that they actually have is they can put some gas into a chamber, establish a plasma that gets to a certain temperature. But then when that plasma ignites into a fusion flame is very, difficult to keep stable. So firstly, maintaining the plasma in a stable way. So basically it can run for a significant amount of time is one of the engineering challenges. And that's why we quite often see press releases saying so-and-so's tokamak operated for record number of seconds. So it's a technical milestone, a technical milestone that's highly publicized and one that's important for the field, absolutely a key step in the way forward. Is it the silver bullet to solve the world's energy problems? No, but an important one that magnetic fusion will need along the way.

David (19:40)

Quickly, tokamak, a phrase again that those outside the nuclear fusion world might not use all that much?

Warren (19:46)

Yep, so tokamak is actually a Russian word. I believe the Russians or the Soviet Union invented the first tokamak as a magnetic fusion device. For the Aussies out there, Australia had the second tokamak outside of the Soviet Union that was based at ANU and was the,l one of the brainchild or a bit of serious research infrastructure installed by Sir Mark Oliphant. Subsequently went on to be the governor of Adelaide and should be a household name if any of listeners don't know the name. But he had one of the few power sources at the time that actually had enough energy to power one of these things, be it any fusion device. So ANU went on subsequently to have several fusion devices, including the first tokamak outside of the Soviet Union, the power supply for that is called a homopolar generator, which if anyone's been to the campus, there's something that looks like a UFO, which is a sculpture in the car park. It's this big, huge iron disc, which was basically spun and ramped up to very, very, very high energies. And then it snapped a big magnet around it to get a few seconds of very, very high power ⁓ current. And that was the power supply that you needed because these devices do need a lot of power. So that most people don't know what that is. They think it's a bit of a weird UFO looking sculpture, but it's...

David (20:58)

It's modern art, it's sculpturally important in some way.

Warren (21:03)

Sculpturally important, but he's a beacon of Australia being a powerhouse of fusion right off the starting line.

David (21:11)

Should be better known. Dr. Warren Mackenzie is our guest today on Where Are We At With? We're looking at where we're at with nuclear fusion. No, it's not just something you might see in the latest Fallout series on Amazon. He is the co-founder and managing director of a company in Australia called HB11. He also has a PhD in things like material science and nanotechnology. I must admit it took me embarrassingly long to work out what HB11 stood for as a non-chemistry and physics student. So apologies for the fact that hydrogen and boron 11, which is literally the fuel that you are looking to use, is the name of the company. It says it right there on the tin. There's a couple of elements that we've spoken about so far, which includes the ignition of the plasma and the maintaining of the fusion reaction. How do you maintain it? How does it continue itself to create the energy that it's releasing?

Warren (21:45)

So this is common to any combustion, fusion or chemical combustion. So let's imagine we're lighting a match. A match will have a bunch of chemical energy. It will produce heat. That heat will be used to ignite the next little bit of water or match head and it will create a propagating, so you strike a match, it creates a lot of heat. That heat will create a chemical reaction with the oxygen in the atmosphere, which will create more heat and that burn will be able to propagate along the edge of the match. In a similar way as a propagating burn in...

David (22:16)

ah

Warren (22:31)

…the combustion of the fuel in your engine or any other, other burn. Definition of combustion is more energy produced than can be released and there's a fuel that keeps it going. In fusion, that's exactly what we want to achieve, except the energy is being released by way of fusion reactions, which are much, more intense in energy, but also more difficult to actually ignite. So when we get to the point where we can get the fuel to a temperature where it will ignite, that ignition will heat enough for it to ignite the next bit of fuel that is quite near it. Now, if that's a magnetic fusion device, that flame will propagate essentially like a low density flame that can be suspended and maybe we can inject a little bit more fuel along the way. In inertial confinement fusion, the propagating burn will literally just consume the high density area of fusion fuel, which is right in the centre. But all that propagating burn happens within, like I said, a few tens of picoseconds.

David (23:27)

As anyone who's tried to set fire to a piece of wood or anything knows, it's one thing to get the initial spark or the initial heat, but to create enough that it can continue to burn itself and effectively set its neighbouring atom on fire, as it were, or combust. That's more heat, more energy, more pressure, more time.

Warren (23:45)

Well, just like chemical fuels, fusion fuels, are easy to ignite, some are difficult to ignite, some produce more energy, some produce less. Coal, for instance, also burns very well, but you've got to get it really, really hot before it actually gets there. Gas is relatively easy, but you do need an intense spark. So the method of ignition and, you know, the conditions to make it burn in an effective way vary from fuel to fuel. And I guess you could almost use the analogy of, you know, how we've actually used fossil fuels, you know. You know, we could use a coal fire power plant, sort of a steam turbine that would run an old train. We can use an internal combustion engine, which ignites a mixture of petrol and air or diesel and air, which uses a little bit of compression, or we use a jet turbine. Lots of different ways, lots of different fuels. And similarly with fusion and different approaches to fusion. The conditions that we need to ignite the fusion are very, different depending on both the approach and also the fuel that we're using.

David (24:41)

Very quickly then, let's talk, you've mentioned the fact that we believe nuclear fusion to be much cleaner than many of the other options. Obviously when it comes to burning fossil fuels, we're not emitting carbon monoxide. Nuclear reactors use a fission process, but one of the downsides to fusion as a number of efforts have postulated is the use of the deuterium and tritium, but that releases its own, I suppose, contaminant radiation of its own.

Warren (25:06)

Harmful thing about nuclear as people perceive it boils down to the presence of neutrons that are produced through a nuclear reaction. So I remember the scene in ⁓ Chernobyl where the firefighter grabs a piece of graphite off the (ground) Now that graphite was used to hold some of the radioactive material. That radioactive material has been shooting neutrons at that for as long as it's been there and that's made the graphite radioactive. So radioactive that when the firefighter picked it up, the neutrons that it was shooting out itself because it's radioactive was burning his hand. So the neutrons are both things that are harmful to biology. They're also things that make other radioactive things. And in the case of spent fuels, the half-life of those is hundreds and hundreds of thousands of years. But that's fission and that's why there's this perception that radioactive waste is a problem and it absolutely is. We move down to the fusion end of the periodic table. Yes, the processes typically produce neutrons. And those neutrons are not as high energy, so they're not going to produce as long-lived radioactive waste. They will produce a little bit, so it absolutely needs a little bit of some containment, but certainly nowhere near the extent that we would see for fission. Hydrogen boron fusion, more difficult to ignite, going back to your question about that, but the hydrogen boron fusion reaction is the only true fusion reaction that produces no neutrons. Far more of a challenge to actually get it to ignite, which is what, know, Hb11 is, you know, is challenged with achieving. But if it will work, you know, we have the benefits of the very, very high energy density fusion or any nuclear fuel, but without any of the downside.

David (26:43)

And some of those downsides can include things like effectively it'll break your fusion reactor over time or break parts of it as the neutrons bombard various aspects of it.

Warren (26:51)

Absolutely. So anything those neutrons touch, they're going to turn into a different material. They're going to erode the material. They need to be contained. need to be safe. There need to be a lot of safety measures in place to make sure that they're contained. Whereas with fusion, this safety bar is much, less. And I guess for anyone interested in politics, a lot of governments right now are actually have legislated the development of new regulation around fusion. And certainly the US and the UK have announced that they are not going to be regulated in the same way as fission does. So from the safety perspective, they're not in the same genre as nuclear fission in terms of.

David (27:32)

What is the Australian government, when you speak to Australian government officials, which I know you do, nuclear power has long been a delicate subject in Australia and at the moment there are literally bans, laws against nuclear plants and the use of some of this material. How does this work given that it doesn't contain any of the stuff that we're trying to prevent against? What's the conversation been like?

Warren (27:53)

So by our assessment and acknowledgement from a lot of people that we've talked to, fission does not fit in the definition of the nuclear ban in Australia. Sorry, fusion doesn't fit into the definition of the nuclear ban in Australia.

Warren (28:07)

Now that's point that we have talked to a lot of people about. And there has been some interest here and there, but given the focus of, I guess, Australia's admirable push for renewable energy, in particular wind and solar and hydro, that doesn't mean their focus is going to be diverted away from that to fusion. That said, Australia doesn't need to. Australia's got a great photonics industry. We've got a lot of expertise in fusion. The first fusion power plants are going to be built as an international mission. And there is definitely interest in Australia's participation in these missions.

David (28:46)

So in a sense, you can aim to effectively be the first to create this nuclear fusion technology which could power the world, but at the moment you're not allowed to do it in Australia.

Warren (28:56)

Well, we're allowed to develop it in Australia. Well, we are allowed to do it in Australia, but, you know, it's not until there's major policy moves expressly supporting it where we'd actually get widespread support. My feeling is that across the world in this race to build the world's first fusion power plant, which is largely being led by the US, we saw Truth Social buy one of the magnetic fusion or the TAE, one of of the of the fusion companies in recent weeks. And that's a really big signal that, you know, the US might be getting very, very real with their investments into public private partnerships. Recently, that I recently went to the IAEA meeting where essentially they're coordinating the milestones that would fit into various different countries milestone based public partnership programs. Europe is expected to, to announce there's this quarter. Germany is investing heavily. So there is this race to develop the world's first fusion power plant. It's bigger than one country and one country's ability to be able to produce it. So it then becomes the topic of an international program. I think with time Australia will jump on the bandwagon of those international programs. For private fusion companies like ourselves, we're essential in this public private partnership equation but we're also developing, I guess, the methods of ignition and what the engine will be for fusion. So we hope to be at the forefront of the technology of choice for one of these first-of-a -kind power plants that are built.

David (30:24)

Yeah. And so where does the money for your company's work, experiments, developments, where does that come from? And does it then enable that technology to be used just by your company in the future? Or is that something that can then be shared with other developers of it?

Warren (30:38)

Well, it's, there's two answers to, well, the first answer is, yeah, we're funding wise, we're a private venture capital funded company.

David (30:42)

Well, there's two parts to the question, so sorry.

Warren (30:49)

So we have private investors. Now we do leverage that money with grants and different schemes, especially the R and D tax credit here in Australia is absolutely brilliant. Australian Research Council has supported us with loads of grants. Fusion Labs around the world have also provided their support with access to large laser facilities that we need to do from experiments. So we're very well supported. We do have a commercial strategy where we will be launching into selling fuel targets for experiments but also laser systems in the future which will be a future way of funding what we do. What was the second part of your question?

David (31:19)

The plan then is that you get to claim the proceeds, the money, you can sell it to other people, the power itself, or is it about effectively being part of the scientific process and sharing information for which you will get some of the funds that come afterwards?

Warren (31:33)

Well, we take money from investors, so we have to make money. So absolutely that's the intention that we own it and we have a business, we develop a business model and we make money otherwise, otherwise we must be publicly funded all the way. And that's absolutely our intention. way now fusion revenues, as into households is some decades off and that's outside of the appetite of most investors. But the nice thing about these milestone-based public private partnership programs is intention is governments will pay large or cut large checks if you achieve strategic milestones on the roadmap to fusion. So that's a really nice way of being able to solve the problem for investors where they're worried about long time frames for their return. While also making sure that the private fusion company community, which are about 50 companies now, are actively solving issues for the development of an industry because solving fusion is far bigger than any one company could achieve, one country could achieve. So of course we want to be the epicentre of the technology development but let's just say we weren't and maybe we were the suppliers of lasers for another program, we're establishing ourselves to capitalise on those revenue opportunities in the future.

David (32:50)

Dr. Warren McKenzie is our guest on “Where Are We At With...?” We're looking at nuclear fusion, his company that he co-founded and is managing director of HB11, hydrogen and boron 11, the fuel that they're hoping to use. Let's talk nuts and bolts and there may not be many of those, I don't know. If we were to picture what a nuclear fusion plant using your technology that you're hoping to make work, what would it look like?

Warren (33:11)

So the actual reactor part would be in the centre but the reactor part would be relatively small. Off the side of that, that central reactor might be a few storeys or maybe five storeys of support infrastructure around it. Now off that there would be four buildings. Those buildings would look like data centres in that they're.

David (33:29)

And what's that look like?

Warren (33:31)

So a big building with people walking around inside doing maintenance, a ⁓ big probably glass building that is a data centre, not particularly inspirational necessarily, but four big buildings that would be essentially wings off the epicentre of the reactor. Now within that, there would be thousands and thousands of lasers. So when we produce these lasers, ultimately the energy that we need to ignite fusion is in the megajoules or tens of megajoules. Right now, very big, a big laser is one joule. We've developed or developing a 10 joule laser with a view to extend it to a hundred or a kilojoule. We would need thousands of those kilojoule lasers to be the energy of the beams combined to actually produce ignition. So we need holes to basically fill up those, the buildings, the four wings off the data centre, which ultimately would provide the energy for the fusion ignition.

David (34:24)

So we're not talking about one or two giant, giant frickin' lasers, but we are talking about lots and lots of quite big ones compared to what we have now combining their powers.

Warren (34:36)

I will fly the flag a little bit for our competitors. Two of our competitors are actually taking a very different approach. Taking a LIGO type, one of them's taking a LIGO type sensor, one of them's taking a big gas tube and trying to turn that into one literally very, very big laser. Our approach is serial combination of lots and lots of lasers, which would would be a different architecture, but we believe it's the one that's most viable and also the one that allows us to start side businesses where these lasers can be used for other things.

David (35:06)

Now, if I'm imagining four effectively large glass, probably sheds almost, coming off the centre of an area, we're talking like a cross effectively where there's four arms. Why that's effectively just two, you don't just need one laser, you're lasing one energy source, you're trying to come from different directions when you're producing that energy towards your fuel.

Warren (35:15)

Yeah. Well, strictly speaking, yes, you could have them in one big area and add the infrastructure of mirrors, very, very big mirrors that actually divert the light inwards. But you need a lot of buildings. You might as well scatter them around a central chamber. Maybe it could be six buildings in

David (35:45)

when we have our lasers working properly, they hit our fuel pellet, as you say, a very small pellet. We're working on the assumption here of success. The energy that is released, how is it released? Is it released in the form of heat, in the form of electricity? And how do we capture that?

Warren (36:01)

So some of our original designs at HP 11, they were very, very small targets. And with small targets, we talked a lot about the idea of direct energy conversion. So we get a fusion ignition from a very, very small target. It would produce charged particles directly. Now those charged particles in principle can be directly converted into electricity. So direct energy conversion is a possibility in principle. It's not really been engineered into a system as yet. Now as our scientific program evolves, the economics pointed us in the direction of actually we need bigger lasers and bigger targets. There's economies that come with scale. As soon as you get big targets, those alpha particles that are released, they bump into things. If they bump into things, they turn into x-rays. We, from our own simulations at the moment, we expect that most of the energy coming out of our fusion reaction would be in the form of X-rays. X-rays are really good, provide a really good transfer of heat. So without significant developments in power engineering, that could just be heating up water or steel for a steam cycle as traditional power plants do. There are also possibilities where they could be used X-ray capture and conversion into electricity. So essentially an X-ray voltaic cell that they could produce. ⁓ Now that's engineering, which is, haven't got to yet, it's some way off, but it's certainly a possibility that despite us producing X-rays that are gonna hit the reactor wall, then alpha particles, which are charged particles, we could directly convert those into electricity.

David (37:18)

Wow. I do like the irony of the fact that the most advanced, challenging, incredible scientific developments happening in the world at the moment are about improving the steam engine.

Warren (37:39)

Yeah, yeah, it's You're not the first person to have told me the same thing.

David (37:45)

Yeah, definitely something you'd hear a lot of. So effectively, it's about trying to create the energy that goes into the lasers, the right conditions. Tell me about some of the challenges. And again, this moves back to your background, which is not nuclear physics as such. But when it comes to material sciences, why is that so important?

Warren (38:03)

So one of the, also material, so I guess I'm a material scientist. When I studied material scientists, I got a little touch on plasma physics, lots and lots of different areas. And I actually started life in semiconductors and electron microscopy during my PhD, which gave me a lot of understanding of particles, their interactions and what happens on the molecular, what happens on the molecular level. guess being the entrepreneur, most of these conversations happen by a scientific team who are far more scientifically knowledgeable about various aspects than myself. But in short, the material sciences still, as with fission, is also a huge, huge issue with fusion. So in particular, reactors where you have neutrons, they're to get radioactive. They're going to have a short life…

David (38:23)

very small things.

Warren (38:50)

…lifetime, that means that these materials have to these, you know, the first wall where basically these particles hit will degrade and they will need replacement during their cycle and they will be radioactive. So that introduces firstly, some radioactive waste that needs to be removed out periodically. Also downtime for the power plant whilst that's actually done. And the lifetime of those things really comes down to material interactions. So to go take one step deeper into the science, I'm going back to X-rays versus alpha particles. One of the reasons we like X-rays. So when alpha particles are very, very high energy, but they will stop in the first couple of microns, maybe 10 micrometres into a material. So you'll have a fusion explosion equivalent to maybe a truckload of TNT and all of that energy is gonna be deposited in your reactor, which may be many meters across, but in the first very, very few microns. And of course, if that energy is gonna be deposited so quickly in such a shallow depth, it's gonna degrade those first walls. X-rays on the other hand, they actually penetrate quite a lot more and they don't actually, they just make it hot. So then go back to the steam cycle, then we can run water through and cool them down and you use that heat in the form of water. So going back to that point, X-rays which are good at distributing the energy deposition over a much, much longer wider area solves a lot of materials issues, radioactive waste issues.

David (39:58)

Kind of what we use them for and other purposes.

Warren (40:19)

Degradation of first world issues, contamination issues in the downstream engineering. It's just to give you a flavour of the reactor engineering that we're looking at.

David (40:29)

There are a number of challenges, no doubt, let's be honest, all of them well beyond the pay grade of people like me. We talked about the fact that effectively you're using a pellet of fuel, the HB11 as a pellet of fuel. How is it suspended? It's not just sitting on a little mat to get shot at. How is it held in place to be hit by the lasers, which obviously need high precision as well?

Warren (40:48)

Yeah, so for inertial confinement fusion, and I guess we'll refer to the results that are produced to propagating fusion burn at the National Ignition Facility, they literally, I mean, they only need one shot, right? So they would suspend this on an arm in a very precise location at the centre of, what was it, 192 lasers that ultimately shoot that. So that's just one. But when you have a power plant and you're need at least one shot per second, these will need to be injected into the chamber. In the case of deuterium tritium, would probably have to be cryogenic. Hydrogen boron, might not need to be cryogenic, but certainly delicate. And they will have to be injected with very, very high precision and with some timing attached to it so the lasers can actually shoot at exactly the right moment. Anyway, the target injection, the target tracking, and triggering of the other lasers that will cause fusion is one of the technological challenges that other companies are looking at, including some of our colleagues at X-Fusion. They do actually have an office in Adelaide, but otherwise they're in Japan. That's a technology that they've made some really, really great progress in. And it's something that every laser fusion company will need eventually.

David (41:55)

And when it comes to, I suppose, the containment of it, I understand you also have been looking at various substances, again, on the material sciences side of things, when it comes to very light, very low density materials, almost like an aerogel that was used. Is that still part of the process that you're looking at?

Warren (42:12)

Yeah, absolutely. So to dive a little bit into what our fusion engine looks like, I guess if we compare it to the National Ignition Facility, they just got a lot of compression and they got so much compression that it ignited. That's sort of like a diesel engine. Air diesel, you compress it, the compression itself is what ignites it. But if we want less compression, like a petrol engine, what do we do? Sorry, I'm putting this one on you David. What do we do? How does...

David (42:34)

I don't know. We add oxygen to it. okay. I thought the spark plug was to create the combustion.

Warren (42:36)

We put a spark plug in there. We put a spark plug in there, and the spark ignites the combustion with less compression than you would need with a diesel engine.

David (42:45)

I've been embarrassed. I've been embarrassed live.

Warren (42:48)

So essentially what we're doing, our approach is sort of like a spark plug. So we also have the lasers that do compression, but then we have another laser that does the ignition. Now the nice thing about the ignition is we can accelerate protons very well with a laser. Those protons are one of the reactants for the hot, the proton boron fusion reaction thing. So we just accelerate protons into the target. We will get a fusion powered spark plug. So going back to foams, why do we care about foams? Well, low density foams are one of the most efficient materials at turning a laser pulse into accelerated protons. And any loss of energy in the system is a big deal. So part of our target will be some of these foams or most likely be some of these foams that as we inject it, they will hit the foam, you know, that foam will turn into accelerated protons to provide the fusion power spark plug that will help ignite the propagating fusion burn as a slightly different concept to what the NIF did, the diesel engine.

David (43:43)

Okay, let's, we're winding up here. I want to talk briefly about the ignition laboratories that actually have produced ignition. They produced more energy as a result of what they did than the energy they injected into the process, but it took a vast amount of energy to get to that point. Is that right?

Warren (44:00)

Yes, absolutely right. So this is the National Ignition Facility, US national lab based in California at Lawrence Livermore National Labs. Now the labs are not designed for energy, they do, a small percentage of what they do is focused on fusion energy production. Their approach, well, firstly, their approach is highly computational. Before we actually even get to the energy that's in them, they actually have now the largest supercomputer in the world called “El Capitan”, which is dedicated to the simulations of how these implosions, how these materials implode. And that's on site. I believe that's at Lawrence Livermore. Now, so they're predicting the best way to do this. Now, they're lasers that they use, flash lamp pumped. So flash lamps think tungsten light bulb. Not very efficient, maybe a fraction of a percent efficient at turning electrical energy to flash those lamps to turn them into laser energy to turn them into fusion. There's a big and one of the biggest factors that will affect the economics of a fusion power plant is how efficient that laser is at turning electricity into light energy. So everyone needs, the entire industry needs to upgrade their lasers to diode pumps. So we're going from tungsten light bulb to LEDs essentially, and a big efficiency here. So the National Ignition Facility, their gain was, their net gain, I think the latest was around five, I believe. Don't quote me on that.

David (45:28)

Okay, so I checked that out. According to the National Ignition Facility's website, energy out was a smidge over four times more than the energy that the lasers put in, but only about 1 % of the electricity required to produce those laser beams. And, fun fact, the NIF Laser Core was also used as a set for the engine bay in Star Trek Heart of Darkness.

Warren (45:48)

But it's been repeated, I think eight or nine times already. So it's a repeatable process. It's not intended to actually be a demonstrator of producing energy. It's meant to be a demonstrator of the science where the results are released to lots of people for their own simulation so they can validate them so science can progress. That's its purpose. And I think as we move from fusion demonstrations to commercial fusion energy where the price of energy is similar to what you pay for on the grid, those added efficiencies which are not the mission of National Ignition Facility but will be the subject of many of these demonstrated facilities being proposed through public-private partnership programs those efficiency demonstrations are going to be really, really key. And that's what companies like us are looking to design.

David (46:32)

Okay, let's finish with a couple of questions about your company and the work that it's doing, including the fact that as you say, you're taking a unique approach of attempting to use hydrogen and boron, isotope boron 11. We know hydrogen is pretty much the most common thing in the universe. What about boron? Is there a lot of that around? And do we have enough? Will we run out like fossil fuels?

Warren (46:52)

We've loads. Anyone who has a mug will probably have a little bit of boron in their mug. Anyone who has an oven that has glass in it, that's gonna be a borosilicate glass. Boron is abundant. It's everywhere. It's dollars per kilo. By our own estimates by the known boron reserves around the world is about 10 000 years’ worth of supply. Boron is absolutely abundant if we can get it to, to burn as the primary fuel which is the challenge that we you know we're founded to achieve.

David (47:21)

And the byproduct of burning hydrogen boron, we mentioned that there will be some, it has to be something that comes out other than just heat or energy, or is there?

Warren (47:29)

Helium. Pretty harmless.

David (47:31)

And we're a little short of that at the moment anyway.

Warren (47:33)

Well, absolutely, we will be short of that at the moment when we turn gas off, because most helium comes from natural gas reserves, there'll be even less of it. Whether it's economically viable for us to collect that helium is a question. But yeah, it turns into helium, which is certainly not harmful for anyone. And if it gets released into the atmosphere, it floats up into the air anyway, which is why we don't normally find it on Earth unless it's contained in a gas reserve.

David (47:55)

I also like the idea of the nuclear fusion plant workers all having high pitched voices.

Warren (47:59)

Yeah. (laughs uncomfortably at the host’s bad joke)

David (48:02)

Okay, so we've talked about that. Let's, without giving too much away from a commercial perspective, what are the proprietary parts of your methods? Where are the proprietary parts, particularly in the process that you're working with? What is it that's being developed by HP11 that's particularly promising?

Warren (48:18)

Well, the fast ignition concept applied for big targets, which we would use for hydrogen and boron. We call them large row R targets. The concept around how we achieve fusion ignition, I guess comparing that to combustion, maybe we're patenting the internal combustion engine with a spark plug, for instance. We've also got patents on, on some intellectual property on some of the reactor design features. One of the important ones is we've got a very, very high efficiency laser that we're developing at the moment. We can't release too much about that, but certainly the designs around that laser, given the high efficiency is such a critical factor in the pursuit of commercial fusion energy, that it's really, really important for us to protect. So we've got an intellectual property position on that. We've also got an intellectual property position on some of the fuels. Now, I guess if we're a company of knowledge, so we're all intellectual property really, with a lot of knowledge in our simulation group, a lot of code in our simulation group, a lot of recipes on how to make fuels such as low density foams. There's intellectual property from everywhere. It will be useful not just for our concept, but many other people's concepts. And like any big complex industry, there might be some intellectual property that we will need from other people as we learn, we come closer to what the actual design looks like.

David (49:33)

And it's been around for a few years now, the company, have been simulations, there's been work done. What are some of the biggest roadblocks that you've faced so far and still need to overcome?

Warren (49:42)

Well some of the biggest roadblocks. Well, we were the first private laser fusion company. We were crazy. We said, of the private fusion, sorry, private laser fusion, now is an industry. We were the first of the private laser fusion companies. And that was at a time when no one really thought the laser fusion would work. Now it's the most promising approach because it's the only one that's demonstrated a burning plasma and net energy gain, as we talked about at NIF.

David (49:47)

What?

Warren (50:05)

So I guess in the early days and a lot of our investors knew this and were very straightforward that, we're funding a science operation. We're trying to find some unknown science in some promising results that no one could explain. And maybe the answer to the world's energy problems were there. It's a very high risk, high reward. And our investors understood that. And we're very happy to happen. Now we've retired a lot of that scientific risk, but, you know, absolutely if you're funding for a science heavy project, fundraising absolutely is a barrier. you know, as keeping our principles of scientific integrity in place, we didn't want to over promise, although lot of other people can be very, very tempted, very, very tempted to do that. In Australia, you know, policy would be a roadblock, you know, without policy support or political support, you know, it's very, very easy to be pushed overseas and there are a lot of people who would willingly pull us overseas.

David (50:57)

But it's not policy, but it's not policy at the moment that's stopping nuclear fusion from happening in terms of the lasers and the ignition and the process maintaining itself. What are some of those that you have to overcome?

Warren (51:01)

Absolutely. Okay, so the major roadblocks are firstly, which we've been working towards, having confidence in the simulations that we have to show that we can produce fusion under the scheme that we have. So we got reactions and particle interactions that are happening in sub femtosecond time frames at high densities. You can't see that, you can't measure that. The only way that you can get any insight as to what's going on is your simulations. And your simulations need to be based, need to be tested against experimental results. So that's building up that understanding, firstly the scientific understanding, updating simulation codes with that new scientific understanding, then using those codes for our target design, for designing the petrol engine, for instance. That's been very, very challenging, but that's something, that's probably our greatest asset right now is that we absolutely know how to do that. Now there are, you know, when you actually look at the economics of a power plant, we've got quite a comprehensive techno economic model. You know, there could be 100 problems that need to be solved. So you can't take all of them on yourself. One of them that we took was the high efficiency lasers. And you know, we've done done very great things. very great things there. I would say looking forward one of the biggest challenges is the plant's going to be big. So if we have a big plant it's gonna need quite a big investment to actually just test that this thing will actually work as a whole. And I think that's going to, so to justify that investment, we need to minimise the risk that it's not gonna work. So we're be very, very sure that we're gonna make sure those simulations are really, really good, make sure we have some very comprehensive engineering, engineering design capabilities to build that up just so we've got a high level of confidence that if we do raise several billion dollars through venture capital or a milestone based public-private partnership program that it will work. So you know forward looking that's a financial challenge that we'll look going forward but that's an issue that's going to face the whole industry not just us.

David (52:53)

Okay, I do know from looking into this that not only is it China, America, Europe, but also smaller countries, Spain, New Zealand, for instance, looking at it, can you at least promise me we'll beat the Kiwis?

Warren (53:06)

We're beat the Kiwis. Yeah, they're doing magnetic fusion anyway.

David (53:08)

Excellent, good to hear. And finally then, it comes to “Where Are We At With…?”, I suppose the most important question is the joke in the nuclear fusion industry, a lot of very funny people I understand, is that nuclear fusion has been 30 years away for about 80 years. What are we thinking at the moment?

Warren (53:26)

I get that a lot. It is 25 years away and it is 25 years away.

David (53:35)

Well, that's exciting and we look forward to coming back to you in 25 years’ time with our podcast as it continues and finding out whether in fact we reached it. Dr Warren Mackenzie, thank you very much for your time today.

Warren (53:43)

Thank you very much, David, having me.

David (53:55)

And a big thank you there to Dr Warren McKenzie, Managing Director and Co-Founder of the company HB11. You can find the links to his company's information on our website, along with a transcript of this episode and previous topics we've discussed on the show. Just go to ww.wawawpod.com. That's www.wawawpod.com Music for the show is by Michael Willimott, production assistance this week from Clare Macmillan. If you haven't already, don't forget to follow or subscribe to this show on your podcast platform of choice. If you liked this episode, please tell your friends or people you're trying to impress. If you didn't tell someone you don't like.

Next time.

Professor Julie Leask (54:39)

There is a whole communication environment out there, particularly emanating from the US, that is augmenting existing worries about vaccines, which we are very likely to see impacts from into the future.

David (54:54)

That's “Where Are We At With Vaccinations”?

Thanks for listening. I'm David Curnow, goodbye.

Managing Director, HB11 Energy

Managing Director of HB11 Energy, Warren McKenzie, PhD (Materials Science / Nanotechnology) is a science entrepreneur, materials scientist and Fellow of the Royal Society of New South Wales. He has held two post-doctorate research positions, at Trinity College in Dublin and at the University of NSW